07.01.25

GMA Insights | Allocation and Attribution: How They Differ and Why That Matters

INTRODUCTION

Companies’ decarbonization strategies often include purchasing low- or zero-carbon products. However, it can be difficult to know what the emissions impact of a product actually is – even if it’s labeled “zero carbon.” It all depends on how the emissions in the manufacturing process were assigned to it. In the very nerdy world of chain of custody approaches (our favorite world), people often use the terms “allocation” and “attribution” interchangeably to refer to two different approaches to assignment. This edition of GMA Insights explains why it’s important to clarify these approaches, their definitions, and the implications of their use.

These two things are not the same.

In the dictionary, allocation is defined as “an amount or portion of a resource assigned to a particular thing” and attribution as “the action of regarding a quality or feature as characteristic of a person or thing.” These definitions guide us to an understanding of two different approaches for dividing a pool of ingredients or their characteristics among the distinct physical outputs of a process.

Approach 1 is the act of assigning physical inputs of a process to the outputs of that process. For example, if you baked a cake that contained four eggs and cut it into four (big) slices to sell, each slice would be assigned one egg as an ingredient. We call this physical assignment allocation. And allocation is always done proportionally because it would be obviously illogical to say that one slice of cake had 4 eggs and the other 3 slices each had no eggs.

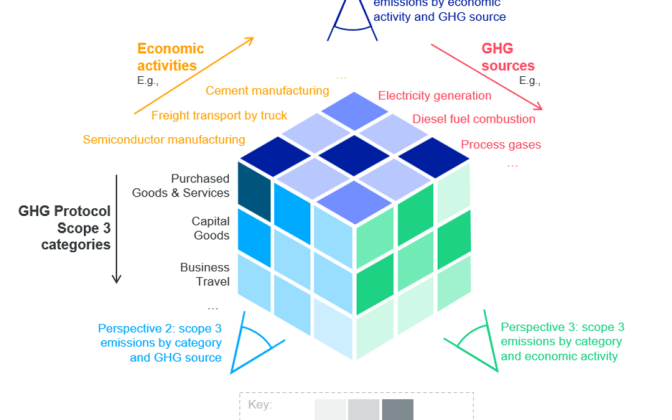

Approach 2 is a bit more complex. It is the act of assigning the “characteristics” of inputs – and of the manufacturing process itself – to outputs (see footnote below). For this reason, we call it attribution because we are assigning qualities or features, not physical inputs. Characteristics can be everything from information about where a raw material was produced to how much carbon was emitted in the manufacturing process. While allocation is always proportional, companies regularly conduct attribution in two different ways:

- 1. Proportionally. Characteristics can be distributed using the same math that is used to distribute physical inputs. Most customers likely assume this is how attribution always works (like allocation), which is one of the reasons the two words are often used interchangeably.

- 2. Freely. In free attribution, the characteristics of all inputs and process impacts are pooled and can be redistributed to the outputs in any proportion desired – as long as the totals for inputs as a whole and outputs as a whole match.

For example, say you’re making a batch of cupcakes. You start with many different ingredients – flour, sugar, eggs, salt, etc. – and you end up with delicious cupcakes. If you sold those cupcakes, how would a customer know what went into making them? They can’t actually see the individual ingredients in a single cupcake, nor is it obvious from looking at a cupcake how or where it was made. That’s where allocation and attribution come in.

Let’s use an extremely simplified batch of cupcakes to illustrate how this might play out:

Say a baker makes a batch of ten cupcakes. The batter for those cupcakes contains ten tablespoons of sugar. The baker sources some of her sugar from Brazil and some from the United States. In this particular batch of cupcakes, the baker uses five tablespoons of Brazilian sugar and five tablespoons of USA sugar. She bakes the cupcakes, and it comes time to package them up.

From an allocation perspective, each cupcake contains one tablespoon of sugar. Ten tablespoons of sugar in the batter, ten cupcakes baked, proportional allocation. Simple enough. But when the baker uses attribution to assign the “characteristic” of where that sugar was produced, she has options:

Option 1: Proportional attribution. The baker could proportionally attribute the “made in USA” sugar, meaning that every one of the ten cupcakes could be labeled “Made with 50% USA sugar.”

Option 2: Free attribution. The baker could attribute all of the USA sugar to five cupcakes and all of the Brazilian sugar to the other five. This means the baker could label five of the cupcakes “Made with 100% USA sugar” and the other five “Made with 100% Brazilian sugar” – even though, physically, all the cupcakes are identical.

IMPLICATIONS

Free attribution can lead to misunderstandings. In the cupcake example above, a customer may not understand that the cupcakes they are buying don’t actually physically contain 100% USA sugar, even though that’s what the label says.

How does this show up in the world of climate action?

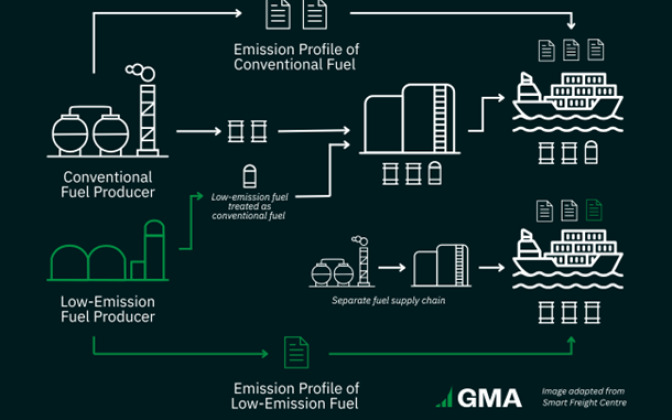

Free attribution can lead to misconceptions about how effectively a supplier has decarbonized a specific manufacturing process. For example, say a steel company improves the efficiency of its manufacturing facility, leading to a 10% reduction in GHG emissions. It could reflect this decrease in emissions proportionally, reflecting a 10% GHG decrease for all steel it sells – or instead, it could sell 10% of the steel it produces as “zero carbon steel ” while leaving the GHG footprint the same as it had been previously for the remaining 90%.

CONCLUSION

When investing in supply chain decarbonization, companies should carefully consider how emissions benefits have been attributed to the products that they buy. This should not be an afterthought, since it could mean the difference between supporting business-as-usual technologies or game-changing new ideas. To date, all the buyers alliances GMA supports have required a proportional attribution approach.

We’ve provided some very simple examples here, but the implications of an approach are not always so clear. GMA is here to parse more complicated situations and help companies decide if the solution being offered is one they want to support. The ins and outs of different chain of custody approaches can be tricky to navigate, and part of our goal with the GMA Insights series is to bring clarity to topics where guidance is sparse or incomplete. To suggest a future Insights topic, learn more about our work, or find out how you can get involved with our programs, email info@gmacenter.org.

See ISO/DIS 13662, Chain of custody – Mass balance – Requirements and guidelines for more on attribution.