01.28.26

Article | Cultivating a lower-carbon food supply chain: Unlocking Scope 3 progress through fertilizer emissions reduction

Authors: Andrew Alcorta and Akhil Mithal (Center for Green Market Activation), Patrick Molloy and Tessa Weiss (RMI)

Agriculture accounts for roughly one-quarter of global greenhouse gas emissions, yet its pathway to achieving net zero defies simple solutions. A wholly climate-friendly food system will require multiple interventions happening in parallel — from regenerative agriculture practices and precision fertilizer techniques to fundamental changes in how we produce the products that help us grow, feed, and support the food we eat. Many of these interventions require behavioral changes across millions of farms that will take time to scale, underscoring the importance of acting decisively where impact can be achieved today. Fertilizer production represents one such opportunity where companies can drive verifiable emissions reductions in the near term.

Nitrogen fertilizers support crops that feed roughly half the world’s population, making them foundational to global food security. The scale of this dependence is stark — without synthetic nitrogen inputs, it is projected that global cereal production would decline by approximately half. While regenerative agriculture practices offer important soil health benefits, relying solely on biological nitrogen fixation would likely require surrendering even more land to crops to maintain current production levels. And the challenge is intensifying: as the global population approaches 10 billion by 2050, fertilizer demand is projected to increase by roughly 35 percent, increasing pressure for continued fossil-linked fertilizer production.

Yet nitrogen fertilizers carry an outsized climate footprint: their production, distribution, and use generate an estimated 1.31 gigatons of CO₂-equivalent emissions annually – the same emissions as consuming 3 billion barrels of oil. Approximately 40 percent of those emissions originate from fertilizer production itself.

Solutions to produce fertilizer with far fewer emissions already exist – renewable-powered electrolysis can eliminate these production emissions entirely – but they cost more than fossil-intensive processes today. Scaling these solutions requires long-term financial commitments that fertilizer producers’ direct customers – input producers and farmers operating on thin margins – are unable to provide. Food and beverage companies face a distinct but related challenge: they need to reduce supply chain emissions, also known as Scope 3 emissions, from the agricultural products they purchase – driven by investor pressure, regulators and sustainability commitments – but lack a mechanism to effectively do so.

The Center for Green Market Activation (GMA) and RMI are launching a pilot book and claim procurement to bridge this gap. In this system, food and beverage companies can financially support low-emission fertilizer projects through the purchase of Environmental Attribute Certificates (EACs) and claim verified emissions reductions toward Scope 3 targets — without requiring physical delivery of low-carbon product through their existing supply chains. Low-carbon fertilizer producers receive revenue certainty to cover green premiums, buyers gain measurable progress on climate commitments, and farmers continue purchasing fertilizer through conventional channels without having to pay more or disrupt their operations.

Scaling technologies to produce low-emission fertilizer

A suite of low-emission fertilizer solutions exists today that can deeply decarbonize production while offering broader benefits like increased supply chain resiliency. Projects like First Ammonia’s in Texas and startups such as NitroVolt, Atlas Agro and TalusAg are pioneering scalable green ammonia production using renewable energy and novel synthesis processes. These technologies can significantly reduce production emissions, increase farmer autonomy over crop nutrition through localized production, and have the potential to reduce input price risk by decoupling fertilizer costs from volatile fossil fuel markets.

However, scaling these solutions faces critical structural barriers. Fertilizer producers need to know they have long-term committed buyers to finance capital-intensive low-emissions projects — but farmers, who typically purchase fertilizer seasonally and operate on thin margins, are unlikely to absorb cost premiums. Further downstream, food and beverage corporations possess both the relative willingness to pay and the creditworthiness needed to support project financing. While low-emission fertilizer currently costs more to produce, the impact on food companies is minimal: premiums would translate to only 1-2% increases in packaged goods prices, far smaller than routine volatility from fuel or commodity markets. Critically, with at-scale deployment, the production cost of green ammonia can decline over time due to learning effects and scale efficiencies.

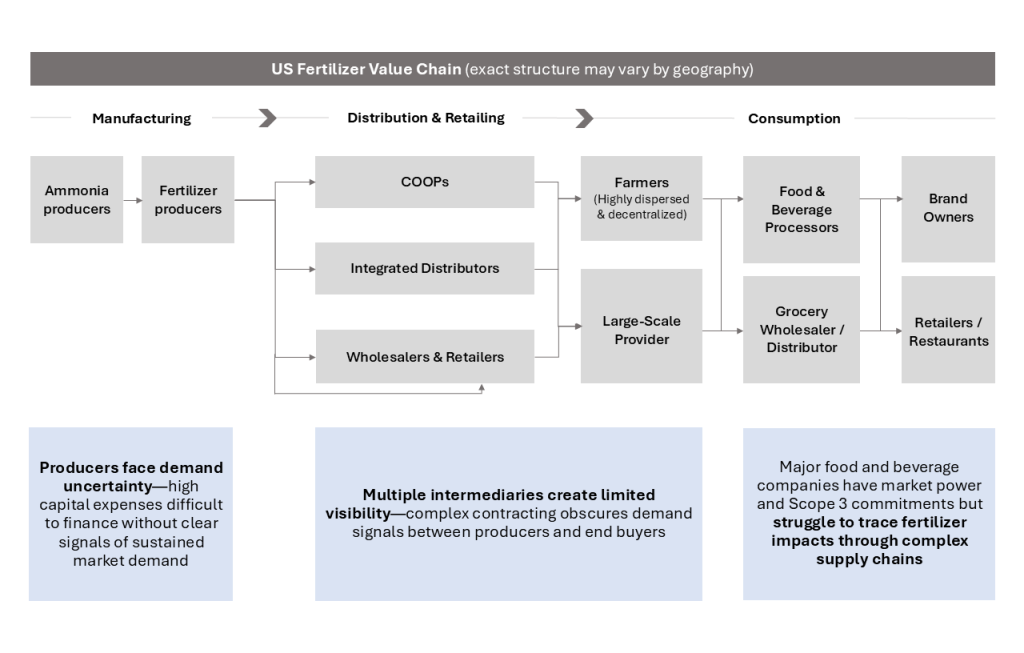

The challenge is that these corporate buyers sit 5-6 steps in the supply chain away from fertilizer manufacturers and have no established mechanism to directly procure or contract for low-emissions fertilizer (Exhibit 1). This long and often fragmented value chain prevents fertilizer producers from monetizing low-emissions production because they lack a relationship with the parties that most value decarbonization.

Exhibit 1: US Fertilizer Value Chain

More than 900 companies across food, beverage, consumer packaged goods (CPG), and agriculture sectors have validated near-term Science-Based Targets under SBTi. Under the GHG Protocol’s Agricultural Guidance, they must account for full value chain fertilizer emissions in their Scope 3 inventories, including fertilizer emissions that can represent a substantial portion of their total GHG footprint. Yet these companies effectively have no way to manage these emissions today: they lack direct relationships with fertilizer producers, creating a gap between sustainability commitments and the operational levers needed to achieve them.

Bridging a Value Chain Gap through Environmental Attribute Certificates (EACs)

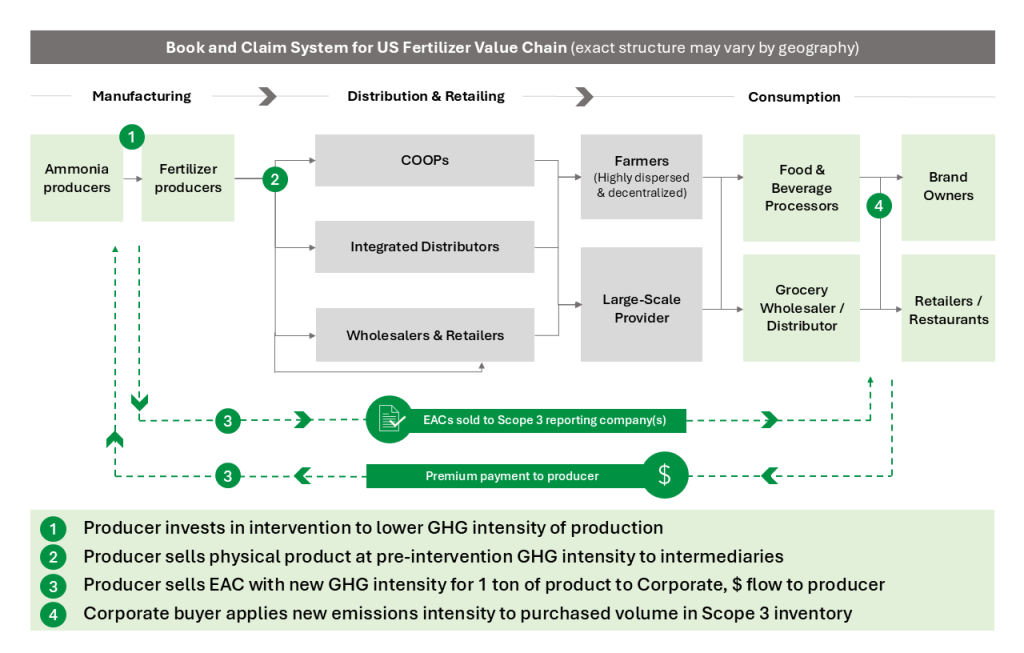

Book and claim systems solve this challenge by decoupling environmental attributes from physical product flow. Under this framework, fertilizer producers generate Environmental Attribute Certificates (EACs) for each unit of low-emission production, which are then sold separately from the physical fertilizer itself (Exhibit 2). Corporate buyers purchase these certificates to demonstrate verified emissions reductions in their Scope 3 inventories, creating a direct financial channel between producers and corporate buyers — regardless of where the physical fertilizer ultimately flows through agricultural supply chains. This structure enables revenue to reach decarbonization projects without requiring companies to engage in complex coordination that alters how farmers source inputs or require that physical molecules are traced all the way through complex value chains.

Exhibit 2: Book and Claim System for US Fertilizer Value Chain

The mechanism aligns incentives across the value chain. Fertilizer producers receive revenue from EAC sales to cover the premium associated with low-emission production, providing the financial certainty needed to finance capital-intensive projects. Buyers gain verifiable, traceable progress on climate commitments through certificates that are independently verified and tracked through registry systems. The physical low-emissions fertilizer enters conventional distribution channels where farmers purchase it at commodity prices, avoiding the need for farmers themselves to spend time sourcing or pay premiums for low-emissions inputs.

GMA and RMI’s Low-Emissions Fertilizer Initiative

GMA and RMI are launching a pilot book and claim procurement to enable fertilizer production decarbonization at scale. By aggregating demand from food and beverage companies with Scope 3 commitments, this initiative will create the collective purchasing power needed to de-risk producer investments and accelerate decarbonization technology deployment. Collaborative buyers alliances can help solve challenges in financing of first-of-a-kind projects by pooling demand across multiple companies, transforming fragmented demand pools into concentrated market signals. This collective approach shares transaction costs, aligns common standards, and delivers the forward contracts that make projects bankable, turning corporate sustainability commitments into impact delivered by real-world investments.

This approach builds on proven models that catalyze investment in new technologies by decoupling emissions attributes from commodity products. Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs) utilized this framework in electricity markets, and similar frameworks are being used for aviation, steel, cement, trucking, maritime fuel, and plastics, accelerating deployment of decarbonization technologies and catalyzing private investment across hard-to-abate sectors.

Across these sectors, success has depended on rigorous market infrastructure. As neutral technical experts, RMI and GMA establish frameworks that balance environmental credibility with commercial practicality — developing clear sustainability criteria for qualifying projects, robust verification protocols, and transparent registry systems that prevent double-counting and ensure corporate investments translate into genuine emissions reductions. By adapting this model to fertilizer, we aim to unlock the financing needed to scale green ammonia and other low-emissions production pathways, addressing one of agriculture’s most entrenched emission sources and giving food and beverage companies a credible path to meet their Scope 3 targets.

Ready to join? If your company has a Scope 3 target that includes fertilizer emissions in your supply chain, this initiative offers an opportunity to achieve your goals and catalyze meaningful agricultural decarbonization. To learn more about participating in the pilot procurement, please contact us at chemicals@gmacenter.org.